Alteration of drug targets by mutation or level of expression can confer drug resistance. Examples include:

Mutations of the topoisomerase II gene alter the configuration topoisomerase II, rendering drugs which target it ineffective.

Mutations that cause the over-expression of enzymes or amplification of receptors can outweigh the actions of a drug at safe dosage.

Drug Efflux removes a drug from the cell before it can accumulate in clinically effective concentrations. An important example of this mechanism is the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family of proteins. This sytem is activated when a drug binds to the transporter protein. ATP changes the conformation of the transporter which pushes the drug out of the cell. This is an important mechanism in the liver, intestine and blood-brain barrier.

DNA Damage Repair (DDR) is a robust and normal process that removes and replaces damaged DNA segments that result from common environment exposures and spontaneous errors induced during DNA synthesis. Many cytotoxic drugs are given to overwhelm the cancer cells capacity to repair the cytotoxic induced DNA damage. In normal cells significant unrepaired DNA damage causes apoptosis of necrosis. However, cancer cells can adapt by upregulating the DDR mechanisms. For example, many tumors acquire an over-expression of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT). This protein increases the tumors ability to remove and correct the DNA damaging crosslinks induced by alkylating agents and platinum based agents.

Cell death inhibition is a hallmark of cancer. Cell death usually occurs from trauma, system failure or through the process of apoptosis. Mutations can cause cancer cells to over-produce anti-apoptotic proteins that enable cells to withstand abnormal levels of physical and chemical stress including: temperature, osmolarity, chemotherapeutic agents, free radicals, nutrient withdrawl, hypoxia, growth factor withdrawl, pro-inflammatory cytokines, DNA damage, aging, etc. Mutations can also inhibit production of pro-apoptotic proteins that would normally trigger apoptotic cell death by the release of cytochome C from mitochondria.•

Principles used to select drugs for inclusion in combination chemotherapy regimens:

- Drugs known to be active as single agents should be selected for combinations. Preferentially, drugs that induce complete remissions should be included.

- Drugs with different mechanisms of action should be combined in order to allow for additive or synergistic effects on the tumor.

- Drugs with differing dose-limiting toxicities should be combined to allow each drug to be given at full or nearly full therapeutic doses.

- Drugs should be used in their optimal dose and schedule.

- Drugs should be given at consistent intervals. The treatment-free in- terval between cycles should be the shortest possible time for recovery of the most sensitive normal tissue.

- Drugs with different patterns of resistance should be combined to minimize cross-resistance.•

Currently, combination chemotherapy is standard treatment for most advanced cancers. However, evidence supporting the benefit of combination therapy is mixed. In the case of breast cancer, an analysis of 12 trials, involving 2317 randomized women, compared the effect of combination chemotherapy to the same drugs given sequentially in women with metastatic breast cancer. The authors concluded, "Sequential single agent chemotherapy has a positive effect on progression-free survival, whereas combination chemotherapy has a higher response rate and a higher risk of febrile neutropenia in metastatic breast cancer. There is no difference in overall survival time between these treatment strategies, both overall and in the subgroups analyzed. In particular, there was no difference in survival according to the schema of chemotherapy (giving chemotherapy on disease progression or after a set number of cycles) or according to the line of chemotherapy (first-line versus second- or third-line). Generally this review supports the recommendations by international guidelines to use sequential monotherapy unless there is rapid disease progression."@

| CAF chemotherapy regimen |

| Days 1-14 |

Cyclophosphamide |

| Days 1 & 8 |

Doxorubicin |

| Days 1 & 8 |

5-fluorouracil |

| Repeat cycle every 28 days for 6 cycles. |

Combination chemotherapy is

given in courses or cycles. The number of cycles vary by type

of cancer, the cytotoxic drugs used, and the patient’s response to therapy.

Combination therapy regimens may be documented by acronym, e.g. CAF (Cyclophosphamide

+ Adriamycin® (Doxorubicin)+ Fluorouracil) is a combination regimen used to treat HER2-negative breast cancer.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is hormonal, cytotoxic or targeted therapy administered after surgery or radiation. It is intended to prevent relapse and improve survival.

Induction or neoadjuvant

chemotherapy is the first treatment, often as part of a standard set of treatments that include surgery, chemotherapy or radiation. It is intended to suppress metastases and reduce tumor burden prior to definitive treatment. Disadvantages of induction regimens rest on the fact that definitive treatment is delayed.@

Induction chemotherapy in the context of liquid (leukemia) tumors, is given to induce a remission. This term is commonly used in the treatment of acute leukemias.

Consolidation chemotherapy involves repetitive cycles of chemotherapy after remission is achieved. The goal of this therapy is to sustain a remission. Consolidation chemotherapy may also be called intensification therapy. This term is commonly used in the treatment of acute leukemias.

Maintenance

chemotherapy refers to using single drugs or combinations

of drugs at lower doses on a long term basis for patients who are in remission or to prevent the growth of residual or remaining cancer cells. The continued cytotoxic effect has been shown to improve survival in acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Palliative chemotherapy is a type of chemotherapy that is given specifically to address symptom management without expecting to significantly reduce the cancer.

Reference

Al-Lazikani B, Banerji U, Workman P. Combinatorial drug therapy for cancer in the post-genomic era. Nat Biotechnol. 2012 Jul 10;30(7):679-92. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2284. PMID: 22781697.

Glimcher, L. (n.d.). Why do cancer treatments stop working? National Cancer Institute. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/research/drug-combo-resistance#combining

©RnCeus.com

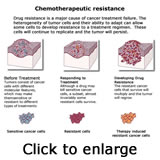

The rationale for combining chemotherapeutic agents is founded on the knowledge that single-agent regimens often result in drug resistance and tumor recurrence. Resistance can occur when cancer cells—even a small group of cells within a tumor—contain mutations that make them insensitive to a particular drug before treatment even begins. Because cancer cells within the same tumor often have a variety of mutations, this so-called intrinsic resistance is common.

The rationale for combining chemotherapeutic agents is founded on the knowledge that single-agent regimens often result in drug resistance and tumor recurrence. Resistance can occur when cancer cells—even a small group of cells within a tumor—contain mutations that make them insensitive to a particular drug before treatment even begins. Because cancer cells within the same tumor often have a variety of mutations, this so-called intrinsic resistance is common.